Name: Ragweed, Common; Ragweed, Great

Botanical Name: Ambrosia artemisiifolia; Ambrosia trifida

Form: wildflower

Parts Used: seeds, greens

Citation: Guenther, K. (2017, January 12) Ragweed as wildlife food [Web log post.] Retrieved: readers supply the date, from http://wildfoods4wildlife.com

Getting Started

I want to help you know more about this foraging option because it ranks #2 on the Super Seeds List. Ragweed—especially common ragweed— is such an important winter food for its seed, because it persists on the plant into winter. And it is high in oil, for those essential winter calories.

It is one of the most important natural birdseeds, so I hope you will take time to learn more about these maligned plants— though I do not intend to minimize the suffering they can cause to folks with allergies.

A common misconception is that the plant goldenrod (Solidago spp.) is the destructive pollen bearer that afflicts allergy sufferers. That misconception comes from the fact that ragweed blooms at the same time as goldenrod. Goldenrod is showier and a very noticeable wildflower, while ragweed is easy to overlook or confuse with another plant.

In this monograph I choose to highlight two species of ragweed, because they both are commonly found, but the leaves and overall plant sizes are so different.

Asteraceae (Sunflower family)

Ambrosia (Ragweed genus)

| Common name | Virginia Ambrosia Species | Origin | Rare Plant Status |

| common ragweed | A. artemisiiolia | native | Not rare |

| lanceleaf ragweed | A. bidentata | not specified | Not rare |

| perennial ragweed | A. psilostachya | non-native | Not rare |

| giant ragweed | A. trifida | native | Not rare |

USDA, NRCS. (2015). The PLANTS Database, National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA. Retrieved on a variety of dates from 2015-2017 from http://plants.usda.gov

Key Features of Common Ragweed

In addition to the identification guide of your choice, here are a couple of features you should see on this plant:

- Between knee to shoulder in height

- Artemesia-like, or flat parsley-like leaf, a fine filigree of small lobes

- Hairy stems

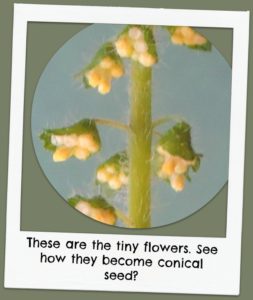

- Vertical racemes of small, almost indistinguishable green flowers, off the main branches. Underside of each flower is yellowish and bumpy, which faces downward towards the ground

Risks

Ragweed pollen is THE well-known human allergen. I have harvested about 1 quart of ragweed seeds each of the past four years. I do not have allergies and it did not bother me. But this year, that all changed. The week after I processed the seed off the plants, I had headaches, fluid behind my eardrums, and dizziness. I trundled off to Emergicare, and was surprised when the doctor suggested I get some Claritan. It had truly not even crossed my mind that I could have developed a ragweed allergy. She explained to me that even though the plant is not producing pollen, I could still be immersing myself in its proteins from the dust and handling of the seeds. It’s the proteins, not just the pollen, that can trigger allergic reaction.

So for those of you who are allergy-free and want to harvest ragweed, I recommend a preventative strategy to miniize your chances of developing an allergy over time. Use a good dust mask and latex or nitrile gloves while handling the plant. And after a lot of contact either during collection or later during seed cleaning, take a shower immediately following your work session.

Key Features of Great Ragweed

In addition to the identification guide of your choice, here are a couple of features you should see on this plant:

- Very tall, 8-15 feet

- Large toothed (serrated) leaves in 3 lobes, lower leaves elliptical without lobes (entire)

- Vertical open spikes of flowers ( racemes) off the main branches, with small green flowers. Underside of each flower yellowish and bumpy, facing downward towards the ground

Great ragweed in bloom, ten feet tall.

About Common Ragweed: For years I confused young common ragweed foliage with young Queen Anne’s Lace foliage. They often grow side by side, in fields and roadside. I eventually observed that ragweed shoots emerge later and start to come to my attention when Queen Anne’s Lace is already flowering, around early July here in western Virginia. By August, the nondescript flower spike of ragweed starts to rise out of the top of the plant which differentiates it further from Queen Anne’s Lace’s umbel flower head. Common ragweed usually grows 1-4 feet tall, about the same height as Queen Anne’s Lace.

About Great Ragweed: I have heard that the great ragweed seed is larger than common ragweed seed, so great ragweed may not be utilized as much by birds as common ragweed is.

The first thing I notice about great ragweed is the leaves with three lobes. (Some lower leaves on the plant do not divide into lobes and are just entire or elliptical shaped.) This 3-lobed leaf reminds me of a toothed serrated version of one of the sassafras leaves. The flower spikes and seeds of great ragweed closely resemble common ragweed. Both can be harvested and prepared the same way to make birdseed. But great ragweed is “great” because of its towering height over one’s head!

Flower Description: Both common a great ragweed flowers are very small, green, nondescript and insignificant and grow along a spike that arises from the main stem and branches. If you look on the underside of the flower which faces the ground, it will be bumpy and light yellow when in bloom.

Leaf Description: Common ragweed grows 1-4 feet tall and has artemesia-like, or flat parsley-like leaves which are fine, filigree lacy-looking leaves. Great ragweed leaves are serrated, with 3 pointed lobes.

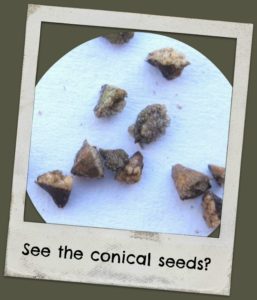

Seed Size: Common ragweed seeds are dried, mature versions of the flower and are conical in shape if viewed with a hand lens and are 5/64 inch (2 mm) diameter. Great ragweed seed has flatter discs, less conical, and are about 1/8 inch (3 mm) diameter.

Harvesting

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| winter | winter | late winter | early spring | spring | late spring | early summer | summer | late summer | early fall | fall | late fall | ||||||||||||||

| seed | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| greens | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

Does this lend itself to being a good enrichment item? Yes! When seed is starting to turn brown and mature, cut whole plants and let dry in a barn or garage on a sheet or tarp. In a few weeks you can install the whole dry plant in bird enclosures. Gently roll the dried whole plants in a sheet and gently handle them to install in the enclosure as an enrichment item. The sheet will catch any of the seeds that do fall off prior to installation. The great ragweed seed I dried on the cut plant was durable enough for careful transport and installation.

Harvesting Seed

I harvest great ragweed in the second half of September. Common ragweed goes to seed a little later, around the beginning of October in western Virginia. When the underneath side of the tiny flowers turn from yellow to tan and the topside of flower turns from green towards brown, it is the time to harvest in either species. In great ragweed, the top 1-2 feet of the plant stalks maybe starting to turn brown as well, while the lower parts of the plant are still green. Soon the seeds will start to fall from the plant. If some of the flower spikes have just the empty remaining flower stalks (petioles) lining it like in the photos, then it is definitely time to harvest, or maybe you are already too late.

Work on a dry day. I find it easiest to cut and dry whole plants, then harvest the seed later. When seed is starting to turn brown and mature, cut whole plants and let dry in a barn or garage on a sheet or tarp for a few weeks. Then, remove the seed from the dried plants. Work over the sheet and pull the plant spikes with the seeds through your hand to pull the seeds off. When done, you’ll have a pile of seed and some dried leaves in the tarp. Transfer this to a bowl and shake and jiggle the bowl so that the seed settles and the leaf bits rise to the top. You can carefully pluck off the leaves. You’ll never get them all, though. Spread the seed in a thin layer on trays and set them out for a few hours in the sun in a thin layer so the last of the insects and spiders can escape. Ragweed seed always seems to have a lot of tiny spiders in it.

If you prefer, you can harvest ragweed seed directly off the plant. In the field, bend the mature, browning plant over a sheet, gently pull the stalk through your hand to dislodge the loose seeds and let dry flower heads fall on a sheet or deposit them in a bucket. Green bits of the seed and husk will come off together. Work each stem of the plant separately. You can come back to the plant in a week or so and try again to get seeds that have ripened after the first harvest.With this plant, after collection in the field, I always find many live insects in my bucket, as well. So, spread out the seed in the sun for a few hours to allow the insects to escape.

Winnowing ragweed is not recommended. You are likely to lose too many seeds. Instead of winnowing, let the birds sift through the seeds and chaff themselves.

How to Store Prepared Seed

Even when dry, the seed sticks together somewhat. Left-over spider webbing gets mixed in with the seed and causes seeds to clump somewhat.

Once cleaned and fully dried, choose a low humidity day—not a rainy day—to jar up your seed. Glass or metal works best, because all plastics are somewhat porous to humidity. Canning jars and lids work well. Place seed in a tightly sealed, glass container and store in a dark, cool area for up to 1 year. Refrigeration and freezing work well. Label the airtight container with the seed name, date of harvest and which animals it should be used for.

If you intend to keep the seed longer than one year, jar up the seeds in two stages. First, jar the seeds up using a desiccant for up to 1 week. Then check the seed for dryness, and if dry enough, remove the desiccant and immediately repack the seed into an airtight container. Read more about drying seeds and using desiccants under the tab “Harvesting, Cleaning and Storage.”

Keep stored seed in an airtight glass or metal container in a cool, dark place. Refrigeration and freezing works well, but allow container to warm to room temperature before opening. Discard any seed that ever appears moldy. See instructions under the tab labeled “Storing Seed.”

Harvesting Greens

Ragweed greens emerge from the ground a little later in the season. In late May, common ragweed is a small plant about 6-9” (15 cm) tall in my area at the ideal time to harvest it as a green. When small, pull up whole plants, leaving root attached. Larger plants will get tougher, but you can still try trimming the softest leaves with scissors of either common or great ragweed.

For fawns, you can try pulling or cutting bundles of whole great ragweed and see if they will go for them in late summer. Offer the plants as soon as possible after cutting, just like you would browse.

How to Store Ragweed Greens:

If you choose to, use a commercial vegetable cleaner or a ¼ cup (60 ml) of vinegar added to wash water as a cleaner. Submerge the plant material and swish it around to remove all dirt from leaves and roots. Rinse in clean water. Always wash greens; you never know what might be on them…like animal feces or urine. Place in a colander or salad spinner to drain, then layout a towel and spread the greens on the towel and roll up the towel. Unroll and transfer the damp greens to storage.

For storage, there are a couple of different possible container methods. If the greens will be used quickly within days, place the spun-and-towel-rolled damp greens to a 1 gallon zip-lock baggie with 12-15 holes cut in it to provide air and keep the greens from molding (or reuse commercial grape bags with holes). Label the bag with the plant name and which animals it should be used for. Keep container in the vegetable drawer of the refrigerator.

For storage longer than one week, use a rigid, lidded, airtight container. After washing and salad spinning the greens, place a paper towel in the bottom, then loosely fill with greens, but do not pack them in. Then lay a paper towel on top and put on lid. Keep container in the vegetable drawer of the refrigerator. Do not use if greens become moldy, slimy or dried out.

Many greens are very sensitive to exposure to ethylene gas, though greens themselves are low emitters of the gas. You may get longer quality by adding with a product that reduces free ethylene gas in the refrigerator. Greens are good until they become dry and crispy, fade in color, or become slimy or moldy.

The term “browse” refers to twigs and sometimes the bark of woodier plants, like trees, but if the leaves or needles are still on the branches, then leaves (greens) can be considered a component of browse.

Read more about storing leafy greens.

Feed Ragweed to:

ragweed | (Ambrosia spp.) | greens |

|---|---|---|

Caution: Human allergen. | ||

Cottontail, Eastern | Sylvilagus floridanus |

|

Deer, White-tailed | Odocoileus virginianus |

|

ragweed | (Ambrosia spp.) | seeds |

Caution: Human allergen. | ||

Vole, Meadow | Microtus pennsylvanicus |

|

Blackbird, Red-winged | Agelaius phoeniceus | strong preference |

Bunting, Snow | Plectrophenax nivalis | strong preference |

Cowbird, Brown-headed | Molothrus ater | strong preference |

Crossbill, Red | Loxia curvirostra | strong preference |

Crossbill, White-winged | Loxia leucoptera | strong preference |

Goldfinch, American | Carduelis tristis | strong preference |

Junco, Dark-eyed | Junco hyemalis | strong preference |

Lark, Horned | Eremophila alpestris | strong preference |

Redpoll, Common | Carduelis flammea | strong preference |

Sparrow, Fox | Passerella iliaca | strong preference |

Sparrow, House | Passer domesticus | strong preference |

Sparrow, Lincoln's | Melospiza lincolnii | strong preference |

Sparrow, Song | Melospiza melodia | strong preference |

Towhee, Eastern | Pipilo erythrophthalmus | strong preference |

Blackbird, Rusty | Euphagus carolinus |

|

Bobolink | Dolichonyx oryzivorus |

|

Bunting, Indigo | Passerina cyanea |

|

Cardinal, Northern | Cardinalis cardinalis |

|

Chickadee, Black-capped | Poecile atricapilla |

|

Chickadee, Carolina | Poecile carolinensis |

|

Dickcissel | Spiza americana |

|

Dove, Ground | Columbina passerina |

|

Dove, Mourning | Zenaida macroura |

|

Finch, Purple | Carpodacus purpureus |

|

Flicker, Northern | Colaptes auratus |

|

Grackle, Common | Quiscalus quiscula |

|

Grosbeak, Blue | Guiraca caerulea |

|

Longspur, Lapland | Calcarius lapponicus |

|

Meadowlark, Eastern | Sturnella magna |

|

Nuthatch, Red-breasted | Sitta canadensis |

|

Pipit, American | Anthus rubescens |

|

Robin, American | Turdus migratorius |

|

Siskin, Pine | Carduelis pinus |

|

Sparrow, American Tree | Spizella arborea |

|

Sparrow, Chipping | Spizella passerina |

|

Sparrow, Field | Spizella pusilla |

|

Sparrow, Grasshopper | Ammodramus savannarum |

|

Sparrow, Henslow's | Ammodramus henslowii |

|

Sparrow, Savannah | Passerculus sandwichensis |

|

Sparrow, Swamp | Melospiza georgiana |

|

Sparrow, Vesper | Pooecetes gramineus |

|

Sparrow, White-crowned | Zonotrichia leucophrys |

|

Sparrow, White-throated | Zonotrichia albicollis |

|

Starling, European | Sturnus vulgaris |

|

Titmouse, Tufted | Baeolophus bicolor |

|

Bobwhite, Northern | Colinus virginianus | strong preference |

Pheasant, Ring-necked | Phasianus colchicus |

|

Rail, King | Rallus elegans |

|

Rail, Yellow | Corturnicops noveboracensis |

|

Snipe, Wilson | Gallinago delicata |

|

Turkey, Wild | Meleagris gallopavo |

|

Book References:

Elpel, T.J. (2013) Botany in a Day (APG). Pony, Montana: Hops Press, LLC.

Martin, A.C., Zim, H.S., Nelson, A.L. (1951). American Wildlife and Plants: A Guide to Wildlife Food Habits. New York: Dover Publications.

Scott, M. (2013). Songbird Diet Index. National Wildlife Rehabilitators Association, St. Cloud, MN.

On-Line References:

USDA, NRCS. 2015. The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 4 January 2016). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

Virginia Botanical Associates. (Accessed January 2016). Digital Atlas of the Virginia Flora (http://www.vaplantatlas.org). c/o Virginia Botanical Associates, Blacksburg.