Name: Chinese Chestnut

Botanical Name: Castanea mollissima

Form: Tree

Parts Used: Nuts, browse

Citation: Guenther, K. (2021, January 12) Chinese Chestnut as wildlife food [Web log post.] Retrieved: readers supply the date cited, from http://wildfoods4wildlife.com

Getting Started

Eastern North America’s grand native, the American Chestnut (Castanea dentata), provided for its neighbors prodigiously—wildlife, domestic livestock and humans alike—all ate chestnuts. According to the American Chestnut Foundation at www.acf.org, “The nuts fed billions of wildlife, people and their livestock. It was almost a perfect tree, that is until a blight fungus killed it more than a century ago. The chestnut blight has been called the greatest ecological disaster to strike the world’s forests in all of history.” Truly, a tragedy of epic proportions.

The fungus, Cryphonectria parasitica, came in on an imported Asian Chestnut into the USA in the early 1900s and 99.99% of the American Chestnut trees—close to four billion trees– were killed by mid-century. At the time one out of every four trees was an American Chestnut. So, the Appalachians basically lost a quarter of their trees—and a food staple— in 40 years.

The American Chestnut Foundation’s mission is to restore the American Chestnut to its ecosystem by making it able to withstand the fungus and survive to maturity so the tree can reproduce again in the wild, fulfilling its niche in the ecosystem.

Today, while we wait to see if a resistant American Chestnut strain can be engineered, the main chestnut that produces chestnuts is the non-native Chinese Chestnut. So, this is the species I discuss in this document.

Fagaceae (Beech Family)

Castanea (Genus)

| Common name | Virginia Castanea Species | Origins | Rare Plant Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| American chestnut | C. dentata | native |

Not listed as a rare plant by the USFWS, but is considered functionally extinct and is listed as critically endangered by the IUCN |

| Chinese chestnut | C. mollissima | non-native | Not rare |

| chinquapin | C. pumila | native | Yes, in some states (not Virginia) |

| chinknut | C. neglecta | native hybrid | Not rare |

Stritch, L. 2018. Castanea dentata. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T62004455A62004469.

Virginia Botanical Associates. (Accessed October, 2020). Digital Atlas of the Virginia Flora (http://www.vaplantatlas.org). c/o Virginia Botanical Associates, Blacksburg.

USDA, NRCS. 2015. The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 20 October 2020). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

Key Features to Look For

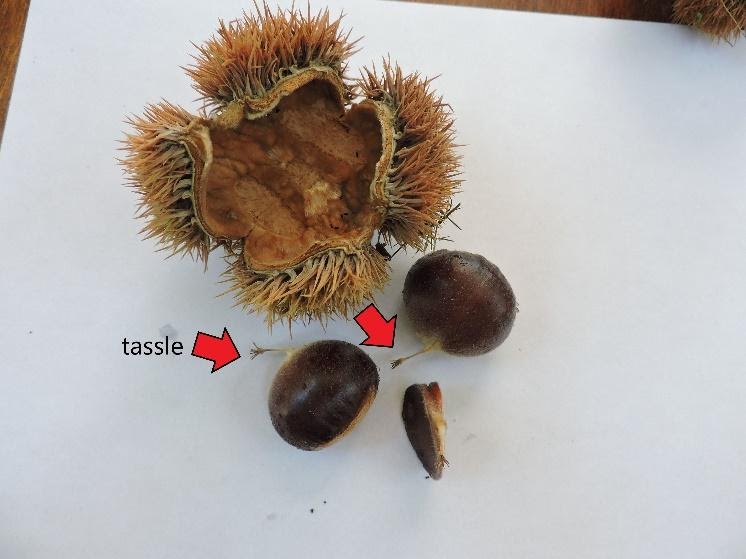

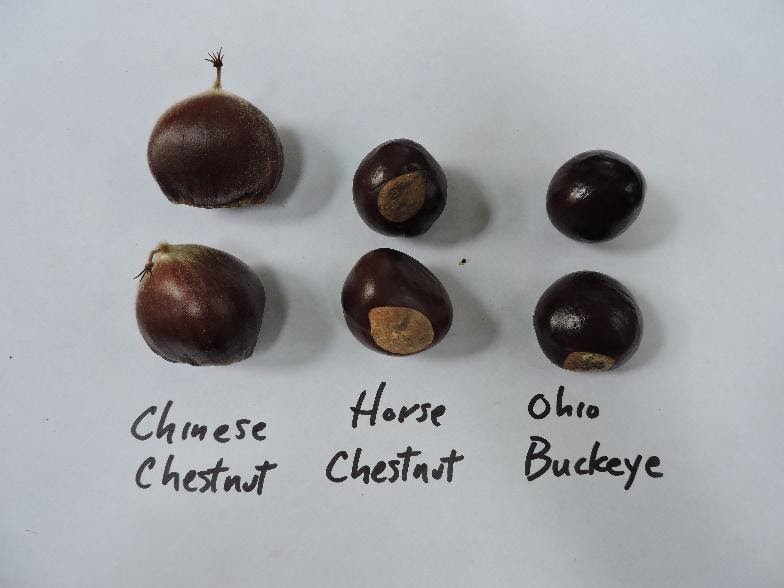

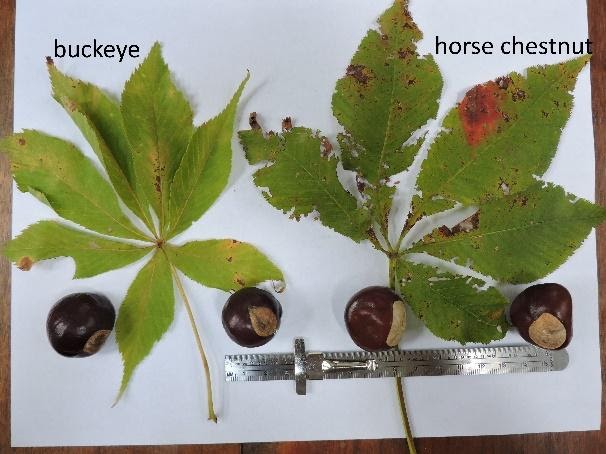

In addition to using the identification guide of your choice, here are a couple of features you should see on the nuts:

- Chestnuts have a “tassel” emerging from the tip of the nut. (Horse chestnuts and buckeyes of the genus Aesculus do not have this tassel)

- Burs (husks) have hundreds of painful spines. The bur opens into four sections to release 2-3 nuts

- Closed burs are somewhat smaller than a baseball

- Nuts are slightly smaller than a golf ball and flattened on one side

- Nutshells are rather thin, shiny, smooth rich-brown color. The nuts have a non-shiny, light color “eye” on one end

About This Species

My experience with a neighbor’s Chinese Chestnut trees is that they are reliable nut producers. On occasional years, the mast will be light or even skip a year, but generally, they produce more nuts than I can harvest—upward of 15 gallons per tree every year. Enough for me to take a lot and know I am still leaving 2/3rds of the nuts for the local wildlife.

Flower Description: Individual white flowers are tiny—as many wind-pollinated flowers are—and form along a long stem. Sometimes you will see the dried flower still attached to the end of the bur.

Leaf Description: The largest leaves are about the size of your hand, and do not lay flat. Semi-shiny on top. Toothed, with a bristle on each tooth. Chinese and American Chestnut leaves are similar, but the Chinese Chestnut leaf is wider.

Nut Size: Slightly smaller than a golf ball and roundish but irregular in shape, flattened on one side.

Harvest

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| winter | winter | late winter | early spring | spring | late spring | early summer | summer | late summer | early fall | fall | late fall | ||||||||||||||

| nuts | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Does this lend itself as a good enrichment item? Yes! Nuts are great enrichment items since the animals have to work at it to dig out the nutmeats. You can make their job easier or harder depending on whether you choose to pre-crack the nuts and to what extent!

Nutrition: From United States Department of Agriculture:

Per 100 grams:

| Water | 61.57 | g |

| Energy | 153 | kcal |

| Energy | 640 | kJ |

| Protein | 2.88 | g |

| Total lipid (fat) | 0.76 | g |

| Ash | 1.14 | g |

| Carbohydrate, by difference | 33.64 | g |

| Calcium, Ca | 12 | mg |

| Iron, Fe | 0.97 | mg |

| Magnesium, Mg | 58 | mg |

| Phosphorus, P | 66 | mg |

| Potassium, K | 306 | mg |

| Sodium, Na | 2 | mg |

| Zinc, Zn | 0.6 | mg |

| Copper, Cu | 0.249 | mg |

| Manganese, Mn | 1.097 | mg |

| Vitamin C, total ascorbic acid | 24.7 | mg |

| Thiamin | 0.11 | mg |

| Riboflavin | 0.123 | mg |

| Niacin | 0.548 | mg |

| Pantothenic acid | 0.381 | mg |

| Vitamin B-6 | 0.281 | mg |

| Folate, total | 46 | µg |

| Folic acid | 0 | µg |

| Folate, food | 46 | µg |

| Folate, DFE | 46 | µg |

| Vitamin B-12 | 0 | µg |

| Vitamin A, RAE | 7 | µg |

| Retinol | 0 | µg |

| Vitamin A, IU | 138 | IU |

| Vitamin D (D2 + D3), International Units | 0 | IU |

| Vitamin D (D2 + D3) | 0 | µg |

When to Harvest Chinese Chestnuts: Nuts in Virginia fall from the tree for a few weeks starting in mid-September. Browse can be harvested anytime.

How to Store Browse

Browse as a term used on this website refers to the twigs and small branches, with or without leaves or needles, of trees, shrubs, vines and other woody-stemmed plants. Browse can also refer to bark, for the animals that gnaw on the bark.

Small trees cannot tolerate very much cutting and survive. The best time to harvest browse for the health of the tree is late fall to winter, but that may not be when you need the browse. The best limbs to remove are ones that rub together and cause abrasions that can make the tree vulnerable to insect damage. Or, cut branches that are overcrowded or hang low to the ground. Prune branches back to the base where the branch meets the trunk to minimize future insect damage to the tree.

Dip pruning shears into a bleach-water solution (1:3) to minimize transferring tree diseases from one tree to the next.

Place the cut end of the browse in a bucket of water as soon as possible after cutting- ideally taking a bucket of what with you as you harvest because the branch will start to close itself off the instant it is injured. Then keep them in water as much as possible prior to feeding, which ideally means even during transport. And keep cut browse in the shade.

Browse cuttings are best fed to animals right away, they do not store well for more than a day before the leaves start to wilt and dry out, especially if it is hot. Read more, at Cutting Browse.

How to Store Nuts

Chestnuts are perishable. They need refrigeration. For my geek-out experiment of nut storage methods, read this: https://wildfoods4wildlife.com/harvesting-cleaning-storage/storing-nuts/ However, in summary, here is the best chestnut storage method of the ones I tried: remove the spiny bur (husk). Soak the nuts in hulls (shells) submerged in water that has a 1/8 cup vinegar added to it. Submerge chestnuts for a minimum of four hours once prior to storage. Drain then roll the nuts around in a towel to mop up the excess water. Allow to air dry. Then refrigerate chestnuts in their shells in a mesh bag or breathable plastic clamshell container. They should last well in the refrigerator for weeks. If mold forms on the nuts, it is a deal-breaker. (The vinegar in the water and good airflow around the nuts help reduce mold onset.)

An alternative for longer-term storage is freezing. Remove the burs and freeze the nuts. The thawed nutmeats will be slightly softer. The nutmeat quality will be somewhat diminished, but still acceptable for use. If you had a large chestnut supply and you could not use them all, freezing a portion would give you some backup.

Other Species

Horse chestnuts and buckeyes are a completely different genus than chestnuts, but the nuts are look-alikes to chestnuts. How can you tell them apart?

- Chestnut burs (husks) are very different than horse chestnut husks. Horsechestnut husks are relatively smooth punctuated by peaks dotted over the husk. Chestnut burs have hundreds of thorny, bristly, ouchy spines.

- The nuts of chestnuts have a tassel on the end of the nut. Horse chestnuts and buckeyes are smooth-ended and tassel-free.

Feed Chinese Chestnut to:

chestnut spp. | (Castanea spp.) | browse/bark |

|---|---|---|

Deer, White-tailed | Odocoileus virginianus |

|

chestnut spp. | (Castanea spp.) | nuts |

Chipmunk, Eastern | Tamias striatus |

|

Cottontail, Eastern | Sylvilagus floridanus |

|

Deer, White-tailed | Odocoileus virginianus |

|

Opossum, Virginia | Didelphis virginiana |

|

Squirrel, American Red | Tamiasciurus hudsonicus |

|

Squirrel, Eastern Fox | Sciurus niger |

|

Squirrel, Eastern Gray | Sciurus carolinensis |

|

Jay, Blue | Cyanocitta cristata |

|

Titmouse, Tufted | Baeolophus bicolor |

|

chestnut, American | (Castanea dentata) | browse/bark |

Deer, White-tailed | Odocoileus virginianus |

|

chestnut, American | (Castanea dentata) | nuts |

Chipmunk, Eastern | Tamias striatus |

|

Cottontail, Eastern | Sylvilagus floridanus |

|

Squirrel, American Red | Tamiasciurus hudsonicus |

|

chinquapin, Allegheny | (Castanea pumila) | browse/bark |

Deer, White-tailed | Odocoileus virginianus |

|

chinquapin, Allegheny | (Castanea pumila) | nuts |

Chipmunk, Eastern | Tamias striatus |

|

Deer, White-tailed | Odocoileus virginianus |

|

Opossum, Virginia | Didelphis virginiana |

|

Squirrel, American Red | Tamiasciurus hudsonicus |

|

Squirrel, Eastern Fox | Sciurus niger |

|

Squirrel, Eastern Gray | Sciurus carolinensis |

|

Jay, Blue | Cyanocitta cristata |

|

Titmouse, Tufted | Baeolophus bicolor |

|

Book References:

Martin, A.C., Zim, H.S., Nelson, A.L. (1951). American Wildlife and Plants: A Guide to Wildlife Food Habits. New York: Dover Publications.

Scott, M. (2013). Songbird Diet Index. National Wildlife Rehabilitators Association, St. Cloud, MN.

Online references:

American Chestnut Foundation. www.acf.org Accessed 12 November 2020.

Stritch, L. 2018. Castanea dentata. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T62004455A62004469. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-1.RLTS.T62004455A62004469.en. Accessed 22 October 2020.

Sullivan, Janet. 1994. Castanea pumila. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station,

Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/tree/caspum/all.html Accessed 1 November 2020.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, NRCS. 2015. The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov), National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA. Accessed 20 October 2020.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. FoodData Central, 2019. (https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/170166/nutrients) Accessed 31 October 2020.

Virginia Botanical Associates. Digital Atlas of the Virginia Flora (http://www.vaplantatlas.org). c/o Virginia Botanical Associates, Blacksburg. Accessed 20 October 2020.