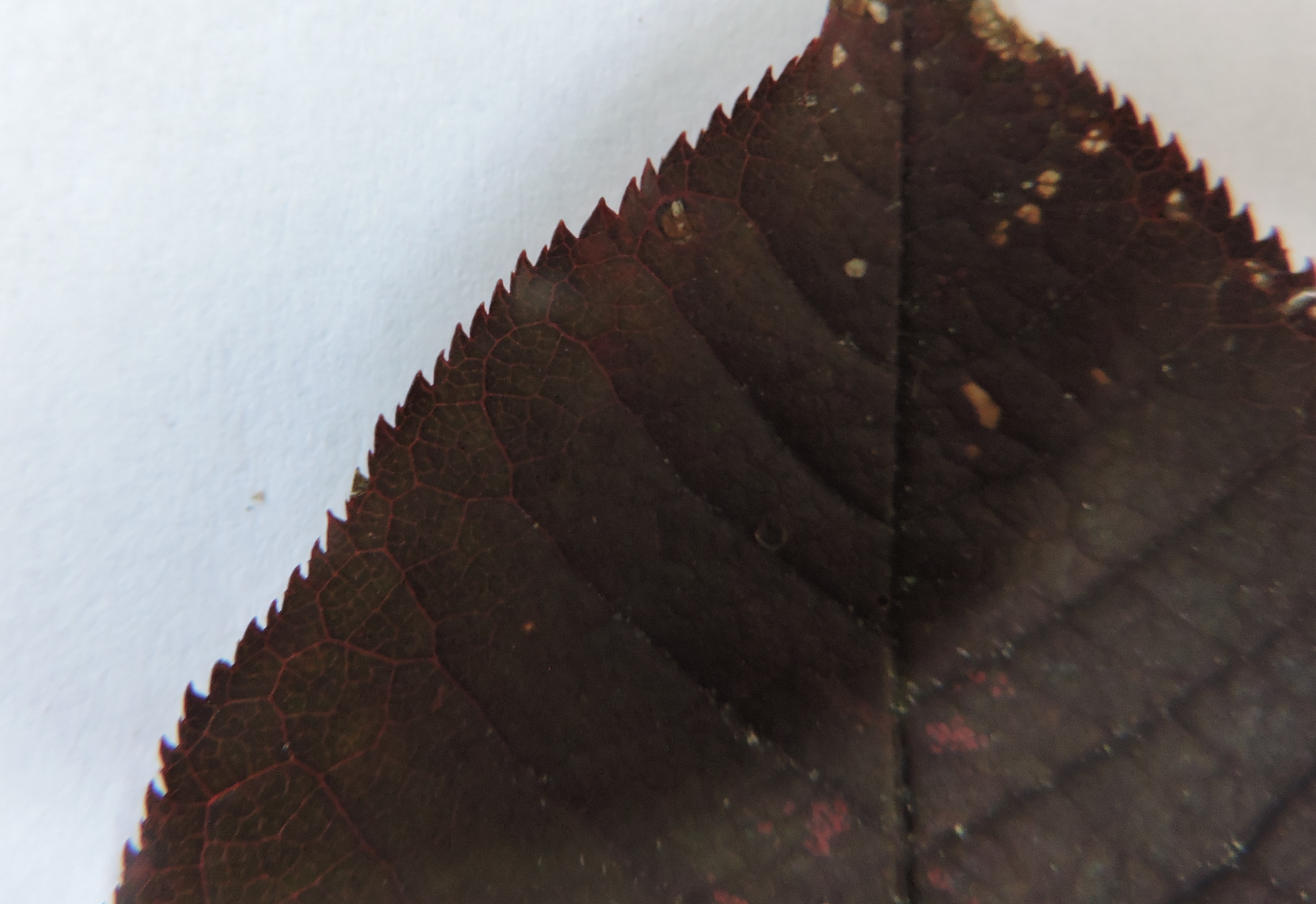

One of the scariest toxicology issues for rehabbers and foragers to be informed about is cyanide, which is most likely to occur when cutting certain browse or greens. To harvest browse means necessarily to cut, move, transport, deliver and store the limbs, twigs and leaves—which creates the conditions of moisture loss and wilting over time. Leaves are the part of the plant likely to be high in cyanide for those plants that contain cyanide compounds. I recommend that any rehabilitator that intends to use any species of cut browse for their patients have a system in place to double check browse ID. It is easier to train staff to recognize the relatively few plants NOT to accept rather than try to learn all the safe plants. I don’t want to oversimplify this complex topic, but below is a quick mantra of questions I ask myself whenever gathering browse. Even this mantra is not perfect to catch every species of cherry. In the southeastern states is Carolina cherry laurel, an evergreen cherry with leaves that appear almost smooth–far from sawtooth edges. And there is Sandcherry (P. pumila), in the northeast and midwest, which has very hard-to-see serrations. And there may be others. Still, this mantra can be a beginner training and awareness tool for folks collecting browse from an array of woodland plants. Plants do not contain cyanide in and of itself. Instead, they have chemicals and enzymes that–when mixed– form cyanide. According to Dr. Charles Stoltenow, Assistant Director of Agriculture and Natural Resources and Former Extension Veterinarian, and Dr. Greg Lardy, Department Head of Animal Sciences and Former Extension Beef Specialist at North Dakota State University, this next list are the some of the worst trees and plants that—under the wrong conditions—have caused cyanide poisoning. No, these are not the only plants that can produce cyanide. But, these may be the worst. The way it works is that if a cyanogenic plant undergoes some sort of destruction that brings the compounds and enzymes into physical contact with each other, cyanide is formed. The kinds of plant cellular destruction that can cause the cyanide to be formed include: When the animal eats the forage that contains cyanide-producing compounds, the toxic reaction may occur very quickly (minutes) or slowly (day), depending on the plant. The cyanide inhibits cells from utilizing oxygen, and basically the animal suffocates. Ruminant animals—like deer— are the most susceptible to cyanide poisoning. In many cases, the young leaves and shoots are the most dangerous time in a plant’s life for producing cyanide. Also, leaves that resume growing after a long, summer drought may be more likely to produce cyanide. Particularly wet seasons can increase risk for cyanide, and some soil types increase risk as well. If you look further into this topic at all–and I strongly recommend that you do– you will undoubtedly read that cyanogenic plants will give off a bitter almond scent when crushed—reminiscent of the scent of almond extract used in baking. This may be true, for some plants and to some people, but don’t count on going by smell. People do not universally smell or interpret smells the same way. For example, some people can smell the scent of asparagus in their urine after eating asparagus. Some cannot. So, due to a lot of variability in ability in human scent receptors, do not go by smell when determining a plant risky for cyanide. I believe I read that somewhere in the range of 2000 plants in the USA can have some quantity of cyanide production. Like all toxic chemicals in plants, cyanide production is a plant defensive system. Animals have ways of countering and detoxifying a small amount of cyanide. If cyanide exposure happens in low quantities over longer period, animals can develop chronic cyanide toxicity symptoms. So as with all things in the toxicology arena, it gets pretty complex. Kevin Aikman analyzed the variability of many different plants in his masters thesis So imagine you are standing on a plot of land and you are surrounded by a plant that is known to be potentially cyanogenic. Even though the plants are of the same species all growing side by side, there can be variability in what percentage of them will actually produce cyanide. Of all the plants in this site’s database that have a cyanide toxicity warning, there still is a lot of unknowns. Plants vary in their potential to produce cyanide based on: And if there is a cyanide reaction: According to the Canadian Biodiversity Information Facility, a lethal dose of hydrocyanic acid (HCN) for humans is between 0.5 and 0.35 mg/kg of body weight. The lethal dose of HCN for cattle and sheep is about 2.0 mg/kg of body weight (Kingsbury 1964). The leaves of black cherry– just about the worst cyanide producer in our area– contain on average of 212 mg HCN per 100 g of fresh leaves. On their website they write, “Symptoms of cyanide poisoning are common to all animals. Symptoms may be minimal, with difficult breathing followed by death. Other signs of toxicity may include a short period of stimulation followed by slow pulse, dilated pupils, spasms, staggering, loss of consciousness, and death, which results from asphyxiation. Postmortem findings include bright red blood and congestion of internal organs (Kingsbury 1964, Scimeca and Oehme 1985).” So, though the mechanisms of poisoning create cellular suffocation similar to nitrate poisoning, with cyanide poisoning the animal’s blood will be bright red and with nitrate poisoning the blood will be chocolate brown, according to Provin and Pitt from Texas A&m Cooperative Extension. Effective veterinary treatment for cyanide poisoning is available , but must be administered right as the poisoning begins. There does exist both field and laboratory testing called a “picrate test” that can measure the amount of cyanide in a plant sample. Read more about that here.Cyanide Poisoning

Three Stop Signs of Cherry

Symptoms of Cyanide Poisoning