The majority of animal and food data in this database comes from four main sources: 1) Marcy Scott’s Songbird Diet Index, 2) Martin, Zim and Nelson’s American Wildlife & Plants, 3) US Forest Service’s website database (www.feis-crs.org/feis/) and 4) observation data from the group Plants for Birds in Louisiana, led by Bill Fontenot, who published their data in the Journal of Louisiana Ornithology. All are used with permission and are copyright protected.

- The Songbird Diet Index also presents which insects and cultivated foods can be used in rehabilitation of songbirds as well as what percentage of a bird’s diet is made up of plant foods versus insect foods. Insect and cultivated foods are not included at this website. So you my want to check out that resource.

- American Wildlife and Plants contains information about what season certain foods were found to have been eaten by mammals and birds, plus it reports the diets from varying regions of the country. For purposes of this website, I have collapsed all the regional data together representing regions east of the Mississippi River. I rank the frequency of use and the preference of a given food based on the highest rating found in any of the regions of the eastern half of the USA.

- The USFS Fire Effects Information System is a US Forest Service website which provides “an online collection of reviews of the scientific literature about [wild] fire effects on plants and animals” and most of the individual plant species listed on this site came from their valuable website. The amount of information available through their collection is astounding. I have used data mostly pertaining to Virginia, but also some other nearby eastern states, at times.

- Plants for Birds in Louisiana Bill Fontenot and a team of nearly 100 observers are documenting and publishing their observations of birds eating fleshy fruits in the wild in Louisiana and generously allowed their data to be included in this website, a significant source of data. Fontentot, W.R. (2017). Avian Frugivory in Louisiana. Journal of Louisiana Ornithology. Vol. 10, pp. 11-40.

There are a growing number of data points being supplied by other individual naturalists, researchers, scholars and professional observers who supply important information for specific species. For example, Susan and Joseph Sam of www.woodchuck wonderland.com have worked to observe, identify and document foods of woodchucks specifically for inclusion in this database. This kind of help and collaboration is invaluable.

The main methodologies for determining wildlife food preferences historically has been through

- direct observation of foraging behavior

- feces analysis and

- stomach contents analysis

Just imagine trying to pick through the stomach contents or feces of a songbird and identifying the half-digested, chewed up seeds! For that reason, even experts can’t say they could list all the foods an animal eats. Foods that are easily and quickly digested may never show up in stomach contents, for example. More durable seeds and nuts last longer in the stomach than greens. So the foods listed at this site are necessarily incomplete. There certainly are other wild foods out there the animals eat that are not listed here. If you know of scientific sources you’d like to be considered to be added to this website if they give permission, contact us and we can look into it.

Which Plants & Animals Are Included?

This website contains over 300 genera of mainly wild plant foods for over 200 species of wild birds and mammals in the search database.

All the birds listed in the Songbird Diet Index who eat wild plant foods are included in this database.

Using American Wildlife & Plants, all the mammals, waterfowl, marshbirds, shorebirds, and upland game birds who live in areas and eat plant foods associated with regions east of the Mississippi River are included in this database.

For genera of plants listed in the above two resources, I further consulted with the The USFS Fire Effects Information System website (www.feis-crs.org/feis/) to corroborate or expand the animal/ plant food usage data. I also consulted this site for each mammal and turtle species in Virginia.

For the most part, this website is geared towards Virginia specifically, and the eastern half of the US more generally. There are some plant listed that are not in Virginia but are in neighboring states.

In most cases, I have listed database entries as I found them in the literature. So, for example, if my source indicated that raccoons eat the species black cherry (Prunus serotina), I listed it as such. Then, I also listed the raccoon as eating Prunus spp. more generally.

However, if my source indicated that raccoons eat Prunus spp. generally without specifying a particular species, I did not list raccoon under any particular species. I tried not to make inferences. I did allow myself to be more liberal making inferences about the part of the plant an animal ate…fruit, browse, greens etc. But if I was at all unsure and my source did not specify, then I listed it as parts unspecified.

Regarding the detailed monographs I choose to write for in-depth information, I made my choices as to which plants to cover based on three considerations:

- what foods have the highest number of species that eat them?

- what plants do I personally have local access to study and photograph?

- what plants will be easy for a beginner forager to identify and to forage?

If you think you find an error in this website, I can double check the source and let you know exactly where the reference came from for any given food/animal and make corrections if need be.

Where is the Information about Toxicology from?

I have based the information on this site about plant toxicity from the following sources which allowed me to use their information. In searching the database, the citation listed in parenthesis after the caution coordinates with one of these sources. When searching by animals, the following icon indicates if a plant has warnings you need to crosscheck in the plant search.

![]()

The warnings listed are for the specific part of the plant listed for the eastern half of the USA. So, there may be toxins associated with other parts of the plant, or the same plants may have risks in other parts of the country or world. Beware.

I generally have tried to list the worst risks I have found for the genus; specific species within any genus may or may not be as toxic. If there is a plant I am aware that has risks, but I do not yet have written permission to share the data, I have written “Caution: This plant has known toxicological risks. Please do more research to determine suitability for your purpose.”

This site does not list human ingestion toxicity info because this site is not about foraging for human foods.

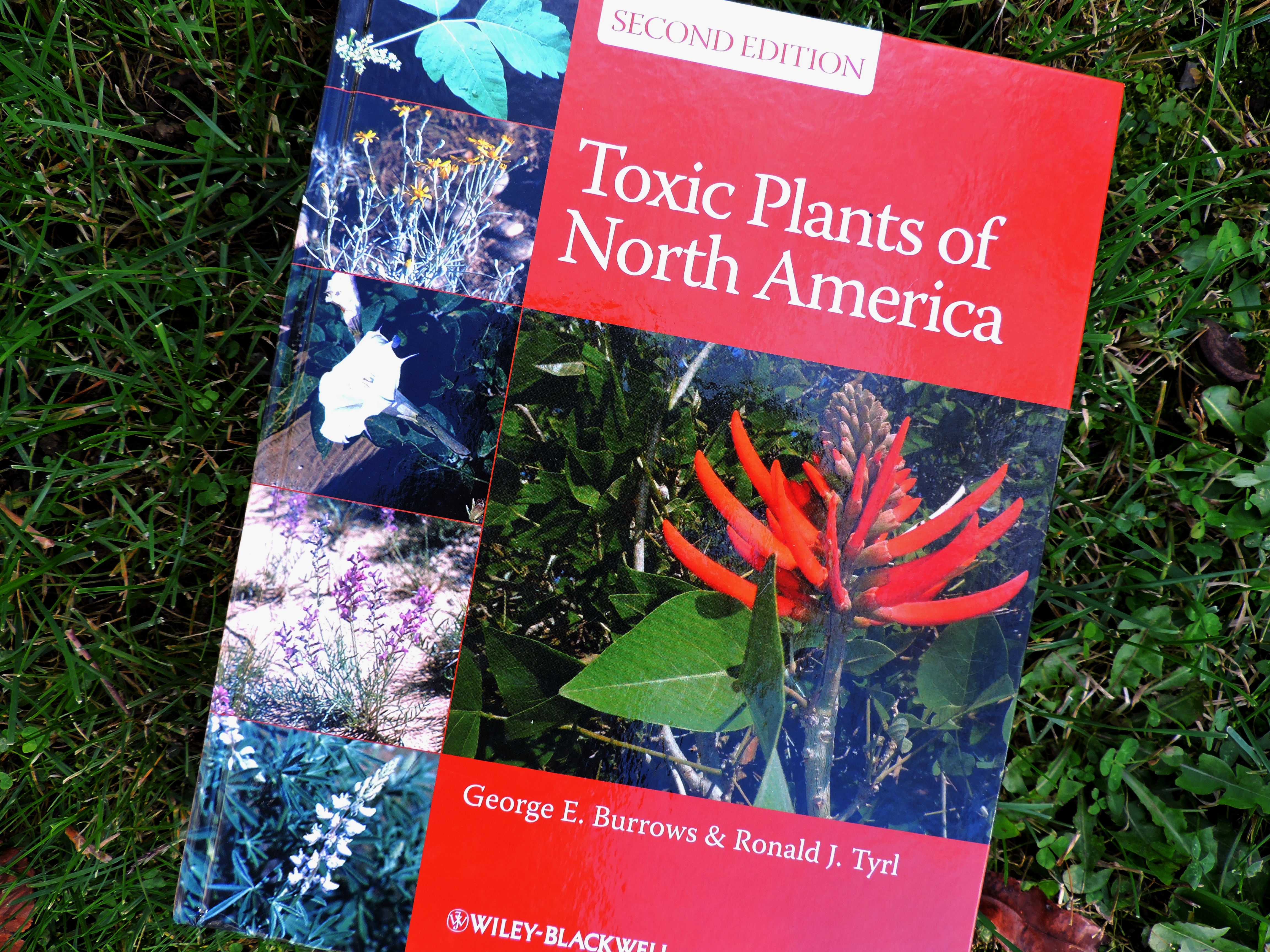

(Burrows, G.E. & Tyrl, R.J., 2013)

Burrows, G.E. & Tyrl, R.J., (2013) Toxic Plants of North America, 2nd Edition, Oxford, U.K.: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. This is a very readable, but very large and expensive comprehensive review of what is known about harmful plant effects on animals and humans. You might find a copy at a university library. Readable by a layperson, but suitable for a veterinarian as well.

(Canadian Biodiversity Info System)

Canadian Poison Plants Information System. (n.d.) Retrieved on 8/6/17 from the Canadian Biodiversity Information Facility at http://www.cbif.gc.ca/eng/species-bank/canadian-poisonous-plants-information-system/canadian-poisonous-plants-information-system/?id=1370403266275

(Cornell University)

Plants Poisonous to Livestock (n.d.) Retrieved August 8, 2017 from Cornell University College of Agricultural and Life Sciences Department of Animal Science at http://poisonousplants.ansci.cornell.edu/alphalist.html

(Douglas, 2004)

Douglas, S.M. (2004, September) Plants reported to cause dermatitis. Dr. Sharon Douglas, of the Department of Plant Pathology and Ecology at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station. Retrieved January 6, 2017 from http://www.ct.gov/caes/cwp/view.asp?a=2815&q=376822

This above link appears to have been removed from the web as of 2025.

(Stoltenow & Lardy, 2015)

Stoltenow, C. & Lardy, G. (2015, March) Nitrate Poisoning of Livestock. Dr. Charles Stoltenow, Assistant Director of Agriculture and Natural Resources and Former Extension Veterinarian, and Dr. Greg Lardy, Department Head of Animal Sciences and Former Extension Beef Specialist at North Dakota State University. Retrieved August 1,2017 from https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/publications/livestock/nitrate-poisoning-of-livestock

Stoltenow, C. & Lardy, G. (2012, September) Cyanide Poisoning. Dr. Charles Stoltenow, Assistant Director of Agriculture and Natural Resources and Former Extension Veterinarian, and Dr. Greg Lardy, Department Head of Animal Sciences and Former Extension Beef Specialist at North Dakota State University. Retrieved March 22, 2017 from https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/pubs/ansci/livestoc/v1150.pdf

The above link appears to have been removed from the web as of 2025.

(Poisonous Plant Database)

FDA Poisonous Plant Database. (n.d.) retrieved 9/25/17 from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/plantox/TextResults.cfm

(Aikman, 1987)

Aikman, Kevin E.,(1987, January 1) Cyanogenic Plants of Illinois. Masters Theses. 2580. Retrieved July 17, 2017 from http://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2580

Provin, T.L., Pitt, J.L. (n.d.) Nitrates and Prussic Acid in Forages. Texas A&M AgriLife Communications. Retrieved October 1, 2017 from http:///forages.tamu.edu/PDF/Nitrate.pdf

The above link appears to have been removed from the web as of 2025.

What Criteria is Used for the Ranking List Entries?

The primary sources usually rated foods in three levels of preference: high, middle and low. But, a plant may be high preference in Michigan but lower preference in Virginia. So the preference factor has some built in limitations. Still, it is factor #1 in the algorithm I used to rank foods.

The second factor in the algorithm considered was how many species of animals eat the part of the plant in consideration. A seed that 29 species eat would outrank a seed that only 5 species ate.

From a forager’s perspective, it would be ideal to collect the most highly preferable foods that feed the widest range of rehabilitation animals, right? Well, maybe not.

Consider if a rehabilitator only works with foxes. To research which foods would be most beneficial in the “fox only” scenario, the only consideration she would care about is the most preferred food for foxes, not how many other species ate it.

So the ranking lists are the most general and broad interpretation of the data. You will want to generate your own lists from the search feature to find out just which plants you want to target for collection.